28 Sep: Scott Williams Videos at ATA Other Cinema

After the recent passing of stencil legend Scott Williams, Other Cinema's Craig Baldwin (I used to call him the Mayor of Valencia Street) wanted to honor Scott during an upcoming OC series. There are several videos here on Stencil Archive that Baldwin will present for the September 28th OC, titled "Psycho-Geo: SF". Craig reached out to me to be a "sort of expert" on Scott's amazing art and talk a bit to present the videos. With an open schedule that day, I could not say no to yet another legendary Mission District artist.

Funny Story: I presented a video and discussed stencils for OC back in 2016. Banksy had just done an amazing run in New York City, and Craig screened the doc "Banksy Does New York". I was asked to talk a bit about Banksy prior to the screening, and mentioned that Banksy was anticapitalist. Scott Williams was in the audience and heckled that statement, claiming Banksy was a sell out. I disagreed, so Scott and I got into a discussion about the topic. I recall walking over to where he was sitting and spending about a minute giving facts about how Banksy had proven that he's not that into the money (one example is his placing a stencil inside a NYC nonprofit thrift store and then telling the NGO that it was there. They auctioned it off for $$$$, and Banksy shop-dropped it for free). I never thought Scott would heckle me, but he was always opinionated and full of surprises. I do not know if I changed his mind. It made for a memorable stencil "lecture".

Here's Craig Baldwin's blurb for the event. Stop by if you want! I will bring a few copies of "Stencil Nation", may dig out some of Scott's cut-outs from the IRL stencil archives, and look forward to the rest of the program that night.

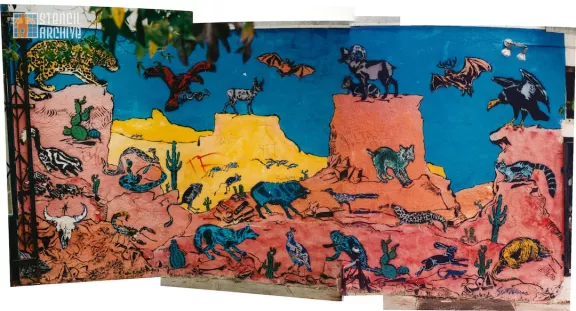

PSYCHO-GEO: SF SEPT.28: HOWZE on SCOTT WILLIAMS + KPR + WILEY + The first of three Focus-on-Locus shows in fact addresses our own situation here in the Bay Area, with a special section devoted to dear departed Scott Williams, long-time denizen of 20th St. in the Inner Mission. One of the greatest stencil artists of our times, Scott passed away in June, leaving behind a true Mission School legacy of obsessively worked paintings--in books, on buildings, in frames, and on the streets. Russell (Stencil Nation) Howze situates Scott's oeuvre within the energized NorCal art-scene of the last half-century, sharing clips from Nick Gorski's "Spray Paint" and Carla Leshne's "Carmanic Convergence". ALSO Arlin Golden is in the house with his hilarious Backyard, to anchor a set of short docs on our Fair City: the Fillingers' Interchange, Attell's Fun House, and Oakland's Down to Earth, on sustainable collective living. AND speaking of utopian projects in the East Bay, tonight's real revelation is a 10-min. prime cut from a larger W-i-P by consummate film artist Ken Paul Rosenthal. PLUS Emeryville MudFlats, William Wiley's billboard art, and free postcards! $12